[Special Interview] Dr. Kendall Brown (North America Japanese Garden Association (NAJGA) Board President)x Tomoki Kato

North America Japanese Garden Association (NAJGA) Board President, Dr. Kendall Brown is known as an influential person in North American Japanese garden research. Dr. Brown plays an important role in educating and spreading information regarding Japanese gardens, and has also written several books on Japanese art. Currently planning his next book and considering the theme of “the vision for future gardens,” he visited Japan. Dr. Brown met with Dr. Tomoki Kato, president of Ueyakato Landscape Co., Ltd. and discussed the current state and future of Japanese gardens and garden craftsmen. While enjoying the scenic garden of bare winter trees, the discussion was held at Junsei Restaurant in the Junsei Shoin (study room), which is a Registered Tangible Cultural Property designated by the Japanese Government. Various topics were discussed in depth, starting with the theme of Dr. Brown’s next book, the motive for this visit to Japan being Dr. Kato’s keynote presentation at NAJGA’s Chicago conference (October 2014), current Japanese garden evaluations, and what will be expected from garden craftsmen.

The Spirit of a Garden Craftsman is “40% Creation and 60% Fostering”

- Dr.Kato

- Welcome Dr. Kendall Brown, thank you very much for coming today. I heard that this visit to Japan is for research on your next book. Will you tell me a little about this book? What is the theme you are writing on?

- Dr.Brown

-

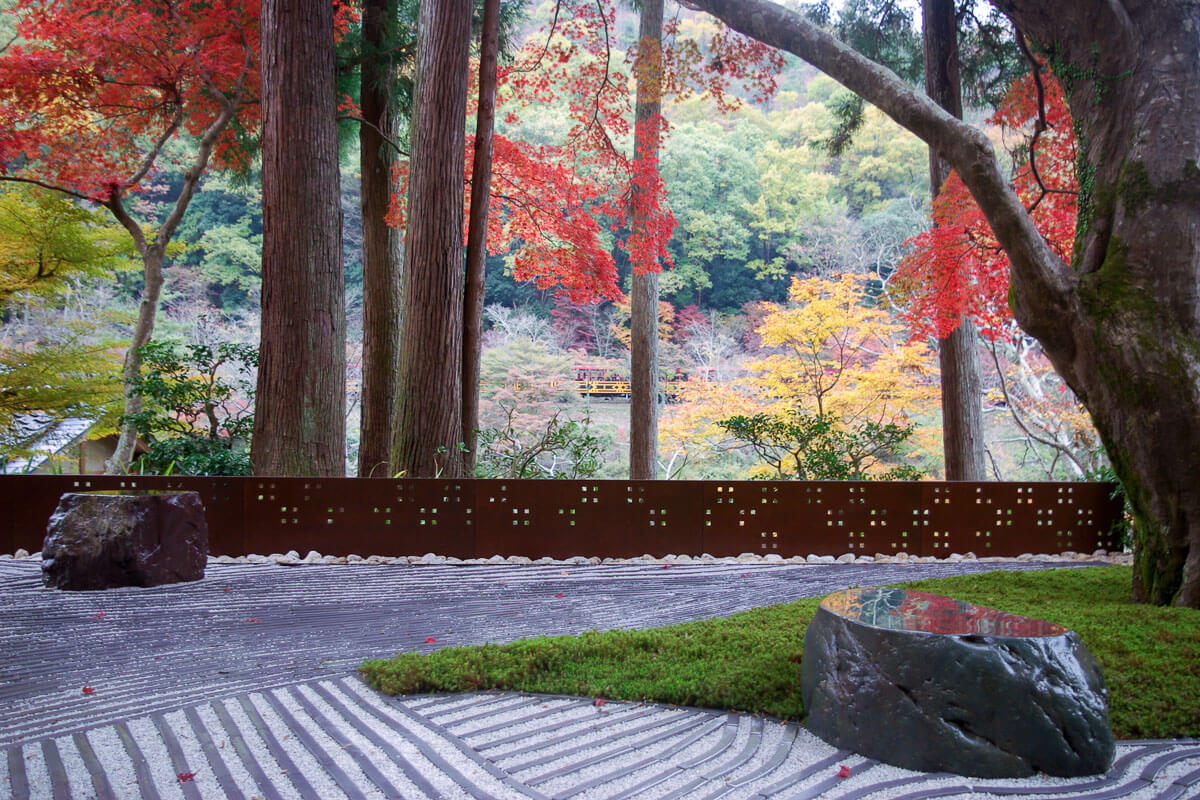

I am currently in the process of writing a book about the future vision of Japanese gardens in North America, and beyond. I want to write about the current state of Japanese gardens, but I do not want to just introduce traditional forms and ways of making gardens. I want to view Japanese gardens of the 21st century as “living landscapes” *1 and think about how we can foster them by reviewing current conditions.

- Dr.Kato

- Your book sounds like it will be a wonderful one.

- Dr.Brown

-

In this next book, I am aiming to shift perceptions of Japanese gardens from the preservation of a “static” traditional art form to understanding gardens as “dynamic: spaces for ongoing personal engagement. Your keynote presentation at the NAJGA Chicago conference about the concept of “fostering,” *2 and the idea that a garden is “40% creation and 60% fostering” is exactly what I view to be necessary for the future of gardens. I was strongly impressed and wanted to discuss the idea with you, so here I am.

- Dr.Kato

- I am honored by your thoughtfulness. Thank you very much.

- Dr.Brown

- I am struck by your new concept of garden “fostering” and the “evolution” of gardens. Fostering a garden for 100 or 200 years from its creation was a new concept for us, but a very important one for the future of Japanese gardens. The message was very powerful because it came from a traditional family lineage of garden craftsman in Kyoto—an ancient city renowned for its long traditions and deep formality. I am very interested in how you created this concept.

- Dr.Kato

- Personally, all the things I talked about are things that I have been doing, considering, and have been conveying in fragments. The roots of my concept come from what I was told by my grandfather as a child, what I was told by my father, and from what I learned in my experience. Yet, my message was not in words that I could teach other people. My father would often just say “anjyou seiyo (just do it properly/accordingly)” but without explaining in what way because that is how craftsmen had been teaching and learning for generations. However, because of increasing company staff and foreigners coming to study as interns, the phrase “anjyou seiyo” is not enough. You have to express the idea in clear, understandable words and that is why I have been feeling it is part of my mission to make this tacit knowledge (unexplainable through words) into shared knowledge. Therefore, I deeply appreciate being given such a wonderful opportunity to make a presentation in Chicago.

- Dr.Brown

- Dr. Kato, I think your concept needs to be more widely known. You have the right message and you are the right messanger. I think many of the participants from the Chicago conference felt the same way. The time is ripe for this message.

- Dr.Kato

- I believe that some of the messages I have been saying in fragments are coming together. These ideas have been told in our profession from a longtime ago. Amongst my father’s generation of garden craftsmen, if you were to put it in words, the message would be “listen to the voices of the trees,” and “listen to the voices of the stones.” I was delighted that what I said was also accepted by the American audience.

Today’s Avant-garde Creates the Future Tradition

- Dr.Brown

- Gardens were originally fostered with passion and existed for the people living with them, and for their guests. However, there are some problems in the status of Japanese gardens in America and Europe. Gardens have become interpreted as “misemono (display things)” or just for passive viewing. They have become like landscape paintings. Since the early 20th century (the late Meiji era), gardens at temples have been open for tourists from 9a.m. ~ 5p.m, like museums. They are a place just to enjoy looking at the scenery and to contemplate “traditional” culture.

- Dr.Kato

- In recent years, this world of private gardens which only a few could enjoy has indeed become more open to a wider variety of people.

- Dr.Brown

- I love gardens, especially Japanese gardens, but particularly gardens that are living gardens, where you can see the garden’s growth from fostering. Gardens were originally fostered with passionate care and should exist with the presence of people living with them. I believe this human-and-garden relationship makes a wonderful garden. A “living garden” is active, vital, and interactive, while a garden only for viewing is passive. I hope that people will continue to pour passion and effort into gardens, and thus receive more back from them.

- Dr.Kato

- In the past, I believe people played more within gardens. I think gardens were a place for amusement and enjoyment. In our daily lives since the energy consumption revolution, the communication we have with nature in our daily lives has been declining. This is fundamentally connected to the difficulty of cultivating the garden craftsmen’s sense of beauty. Especially since the Heisei era (1989), I feel this has become a serious problem.

- Dr.Brown

- The other problem Japanese gardens face is that there is a strong pressure to maintain the Japanese garden heritage just as it is—to protect it by preserving it. Although some old gardens should be preserved, it is very hard to create a new style within tradition under these conditions. Using such an approach, people such as the garden craftsman the garden craftsman Shigemori Mirei *3 and Japanese-style painter Kawabata Ryushi *4 probably would not have succeeded in creating a new style within tradition.

- Dr.Kato

- This does not just affect the field of gardens. The heartful professional craftsmen of Kyoto also know that “preserving” and “inheriting” are not enough. For traditions to truly live on and thrive, they must continue creating new things. By taking something that is “everlasting” (a universal thing) and adding “fashion” (a new trend) is our understanding of how traditions can truly live-on. However, not eveyone feels the same way about this topic.

- Dr.Brown

- I agree with your point. Just protecting or maintaining is easy, and creating something new is also fairly easy. Dr. Kato, I believe what you are trying to do, “creating new value within tradition,” is very challenging, but it is the ultimate goal. I wonder what prompted you to try to do this. Dr. Kato, you attended graduate school in your 40s, and finished a doctoral course. It is uncommon for a garden craftsman to attend a graduate school in their 40s, is it not?

- Dr.Kato

- My professor, Dr. AMASAKI Hiromasa *5 led me to this decision. Dr. Amasaki was a former garden craftsman who worked on sites and then changed to the study of experimental fields. In order to educate the younger generations, Dr. Amasaki created the online Research Center for Japanese Garden Art and Historical Heritage course at the Kyoto University of Art and Design. With his advice, I decided to attend graduate school at the age of 42. There I studied and relearned the leading research regarding Japanese gardens.

- Dr.Brown

- I imagine that the knowledge and experience you gained from attending a graduate school influenced your work and helped establish this philosophy.

- Dr.Kato

- Yes, indeed it has. I would say both sides influence each other: the perspective of working on-site in an actual garden and the academic perspective. Especially the philosophy that a “garden craftsman takes 200 years” was formed from what I learned through research. Now, I often use the phrase “it takes 200 years to become a true garden craftsman.” Through what I learned from research, I realized even more the deph of the world of Japanese gardens. I truly felt that “life is too short, to fully comprehend the art of gardens.” In order to come close, I think it is important to learn from the tradition and learn from the team. We must learn from great people in the past, such as Muso Soseki *6, Kobori Enshu *7, and learn from new designers. We also learn from tarako spagehtti.

- Dr.Brown

- What, tarako spaghetti too?!

- Dr.Kato

- Yes, spaghetti which is a foreign food culture and tarako (salted cod roe) is a Japanese food culture. The combination of these two very different food cultures have created a new delicious dish. (Laugh)

- Dr.Brown

- Aha, indeed. (Laugh) Ueji’s gardens combine modern aspects within traditional forms. I think he was creating within tradition.

- Dr.Kato

- Exactly. Do you know the Kogetsudai (Moon-viewing Platform) at Ginkakuji (Jishoji) Temple?

- Dr.Brown

- Yes, of course.

- Dr.Kato

- During my keynote presentation at NAJGA, I said ‘who do I want to meet?’ if I could time travel to the past. I named 3 men who are well known; Kobori Enshu, Muso Soseki, and Ogawa Jihei (7th generation) *8 . It is true that I wish I could meet them, but I have one more person: my secret number one person I want to meet.

- Dr.Brown

- Oh? Who might that be?

- Dr.Kato

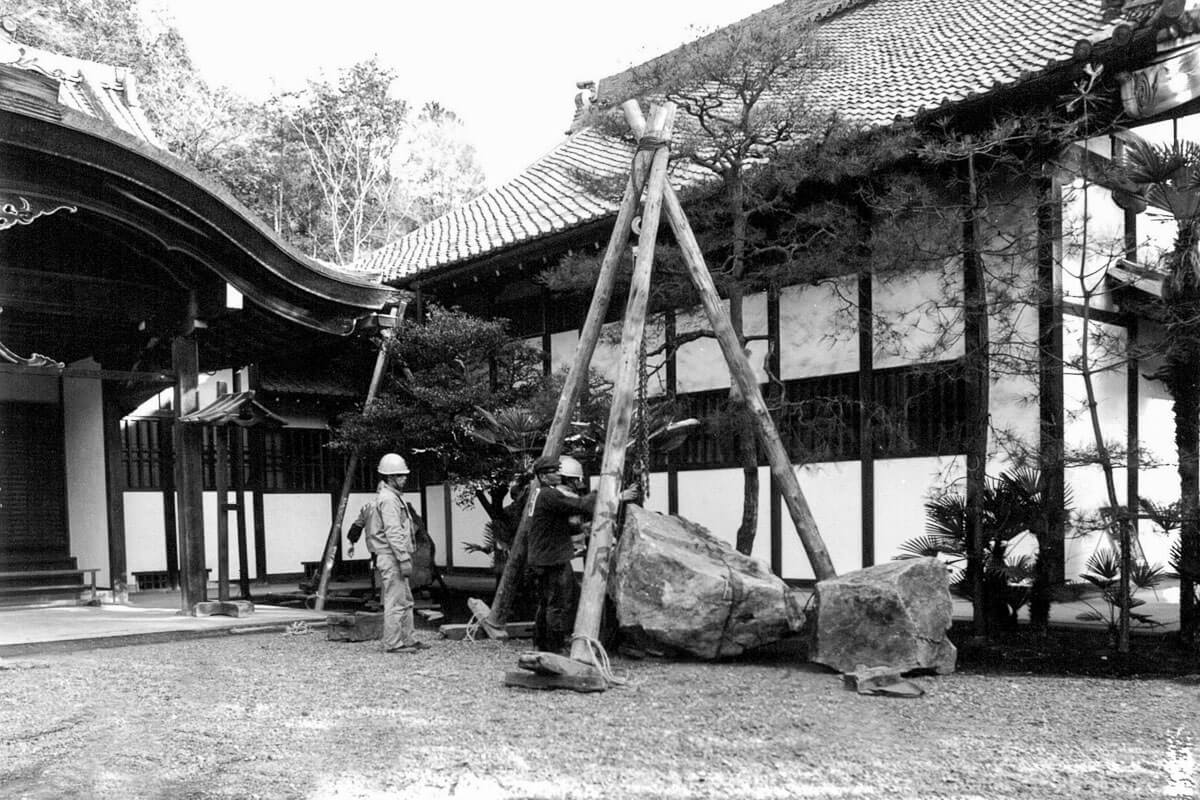

- The person who made the Kogetsudai and Ginsadan (sea of silver sand) at Ginkaku-ji Temple *9 Those forms were not in the garden when it was first built, but added later. One day, when the pond was being dredged (cleaned), a succeeding garden craftsman decided to play a little by piling the white sand into a mound. Someone saw that and felt it was beautiful, hence it remains till this day. There is no record of the person’s name or original purpose for the mound. In this fashion, a humble garden craftsman made a new tradition. I think, perhaps, that is what is most important. Something that is surprisingly original is loved by the world and after 100 years it has become a tradition. My aim is to create a similar effect, such as “today’s Kogetsudai.”

- Dr.Brown

- That is absolutely wonderful.

The 21st Century’s Classic Landscape is Japanese Gardens

- Dr.Brown

- In Europe and America, the popularity of Japanese gardens started because they were exotic within a culture of orientalism. In the era of great international expositions held from the mid-19th century until about 1940, the Exposition Universelle of 1889 in Paris was a symbol of this trend. Japan’s exhibit at these overseas expos always included a Japanese garden that captivated many westerners. Japanese fine arts and crafts such as lacquer, woodblock print (ukiyoe), Japanese-style paintings (Nihonga), ceramics, and the like also were captivating. The trend saw chinoiserie (the style in art reflecting Chinese influence) replaced by Japonisme.

- Dr.Kato

- It was also a time when Japan met Western culture and went through cultural englightenment.

- Dr.Brown

- The postwar era was a time that many sister-cities were created, and this trend created new Japanese gardens all over America as well. However, when the establishment of style (form) falls into a pattern of stereotypes, you often lose the original qualities you admire, and also, freedom, and thus the ability to grow. In this day and age, I think more emphasis should be placed on the fundamental values of Japanese gardens.

- Dr.Kato

- Why are Japanese gardens this popular? What do you think are these values of Japanese gardens?

- Dr.Brown

- Well, let me give one example. In the book, The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective *10, on the human understanding of the environment based on perceptual psychology, the authors Stephen and Rachel Kaplan show that there are certain kinds of environments where people feel stress, and other kinds of environments that create a kind of relaxation where we are refreshed. The complex bustle of activity in a city environment creates stress. So, in what kind of environments do humans feel a sense of mental relaxation? There are six characteristics of restorative landscapes. The first is “prospect and refuge,” the combination of an open view and somewhere you can hide. The second characteristic is balanced composition of space that is orderly and easy to understand. The third is mystery, a space we cannot fully comprehend, so we are intrigued to explore it. The fourth is a “soft fascination” created by things like rustling leaves in the wind, or the contrast of light and shadows. The fifth is a sense of human conncetion, allowing the feeling that we can comfortably enter in and exist out of that scenery. Lastly, the sixth characteristic is that there is water, a variety of plants, and blue and green colors. These characteristics all point to gardens, but more specifically, to the landscape of Japanese gardens.

- Dr.Kato

- Oh, that is very true.

- Dr.Brown

- The value of Japanese gardens is that they reflect an ideal natural environment. Western style gardens are wonderful, but they have a more man-made feel to them. All gardens are important for our lives, but Japanese gardens have remarkable characteristics. With today’s progress of globalization, both flattening the world and increasing our sense of alienation, the value of and need for Japanese gardens is increasing.

- Dr.Kato

- Ahh, that is very interesting.

- Dr.Brown

- Today, in the music world, the word “classic” represents a genre of music that is basically European orchestral music art of the 17th to 19th centuries. This “classical music” has became a universal music that is loved worldwide, accepted, and familiar to everyone. I think Japanese gardens have equally fundamental values in the visual world. For this reason, I believe that Japanese gardens should and will increasingly become a “classic” for design in the 21st century.

- Dr.Kato

- Uh-huh, classical music!

- Dr.Brown

- Yes, the word “classic” originally comes from Latin and means of the highest class, and also has the nuances of being old, and standard, as well as everlasting and universal. Just as European orchestral music became “classic” in the genre of music, I deeply hope that one day the concepts of Japanese gardens will become a classic in the genre of refreshing or relaxing landscape. Classic landscape may be an idea used by the next generations. It is my hope that someday, people around the world will look at, and interact with, high-quality Japanese gardens and feel a sense of fascination that is deeply restorative.

- Dr.Kato

- So, a “classic landscape.” That is a wonderful concept. I am deeply inspired by this. I feel it presses my point on just how important it is for Japanese garden craftsmen and Kyoto garden craftsmen, like myself, to continue devoting our spirit and focus on “fostering” as we re-embrace our roots. Thank you very much for your time today.

- Dr.Brown

- Oh no, the pleasure was all mine. Thank you very much.

Dr. Kendall Brown

Current Board President, North America Japanese Garden Association (NAJGA). Professor of Asian Art History in the School of Art at California State University, Long Beach.

Profile:

Born in Kyoto City 1966 and the 8th generation of this garden company founded in 1848 and fostering gardens for over 160 years. The company regularly takes care of national cultural treasures; Nanzen-ji Temple, Higashi Honganji Temple, and Chishaku-in. In addition, conducting maintenance, revival construction, and creating gardens for numerous villas such as Murin-an and Tairyu-Sanso, located near Nanzen-ji Temple. In recent years, the company has been designated by Kyoto Prefecture to manage and operate the Keihanna Commemorative Park. The company aims to be an excellent three-in-one role model for work site, research, and management in the field of landscape architecture. Graduated from Chiba University, Faculty of Horticulture in 1990. Obtained a Ph.D. from Kyoto University of Art and Design in Landscape Architecture in 2012. Doctoral thesis “A Study on the Spatial Features of Shosei-en Garden of Higashi Honganji Temple” received the 2013 Japanese Institute of Landscape Architecture Award. In 2014, attended the North America Japanese Garden Association (NAJGA) conference in Chicago as a keynote presentator and is actively spreading the spirit and skills of Kyoto garden craftsmen.

January 16, 2015 Recorded at Junsei Restaurant in Sakyō-ku, Kyoto City

Cooperation: Junsei Restaurant

Photo: Yoshiyasu Nishikawa

Witter: Yoko Fukuda

Translated: Eureka Kobayashi

*1 “Living landscape”

“Living landscape” theory is by Tadahiko Higuchi, a landscape scholar who wrote a book, The Visual and Spatial Structure of Landscapes, that analyzes the scenic view of Japanese gardens from a landscape engineer’s perspective. In it is a passage on how landscape elevations are perceived in different stages, so naturalistic terrain is “thinking” but not in the meaning of a cognitive stage, but rather as a scenic landscape that you can “live” and “experience” from inside. In this remarkable cultural theory, the “living landscape” in “Japanese landscape scenery” is considered as a habitat that we prefer, or are attracted to live in.

*2 NAJGA

North American Japanese Garden Association (NAJGA), founded in 2007 to share common problems and assignments that Japanese gardens in North America face as well as nurturing the gardens craftsmen. In 2012, signed a cooperative aggreement with the Academic society of Japanese garden, creating strong ties with Japan. In October 2014, Dr. Tomoki Kato gave a keynote presentation, included were new concepts of “fostering” and evolutions.

Outline and summary “The Spirit of Kyoto Garden Craftsman” keynote speech

*3 Mirei Shigemori

Mirei Shigemori (1896 ~ 1976), a landscape architect from the Taisho to Showa eras, who designed over 100 gardens at tea rooms, shrines and temples, homes, and hotels. His masterpieces include the Hojo Garden at Tofukuji Temple and the garden at Matsuo Taisha. He left remarkable books, such as the compiled research on all of Japan’s famous gardens in his 26-volume study Nihon Teienshi Zukan (published in 1936 ~ 1939), and the collaborative 35-volume, Nihon Teienshi Taikei (published in 1971 ~ 1976), among other works.

*4 Ryūshi Kawabata

Ryūshi Kawabata (1885 ~ 1966), a famous Japanese painter of the Nihonga style from the Taisho to Showa era. He started by studying western art, but changed to Japanese art after his visit to America. His ideal was a bold, liberal expression on a large scale and advocated for Art for the Exhibition Place. He established a new Nihonga lineage called Seiryusha and was a prominent figure outside of the government exhibitions. He recieved the Order of Culture from the Japanese government. His noted works include “Naruto” (Whirlpool) and “Aizen” (Indulgence in Love).

*5 Hiromasa Amasaki

Hiromasa Amasaki (1946 ~ ), is a landscape architect and professor at Kyoto University of Art and Design and department head for the Research Center for Japanese Garden Art and Historical Heritage at the same university. His specialty is Japanese garden cultural history, garden design, and landscape design. Some of his publications include Ueji no niwa (author and editor 1990), Ishi to mizu no ishi (1992), Niwaishi to mizu no yurai (2002), Gardens created by Hiromasa Amasaki (2006), 7th Generation Ogawa Jihei (2012), and many more. He has received such awards as the Japanese Institute of Landscape Architecture (1992), Kyoto Prefecture Cultural Award (2007), the Kitamura Award from the Parks & Open Space Association of Japan (2010), and the Academic Society of Japanese Garden (2011).

*6 Musō Soseki

Musō Soseki (1275 ~ 1351), Rinzai Zen Buddhist monk from the late Kamakura to the Nanbokucho periods. The progenitor of the Muso style (Saga sect style), he recieved patronage from powerful men such as emperor Go-Daigo and Takauji Ashikaga. He not only took part in the creation of Tenryuji Temple garden in Kyoto, but was also a renowned garden craftsman of the middle ages, creating gardens for Zuisen-ji Temple in Kamakura and the Saiho-ji Temple in Kyoto. His famous texts include Dialogues in a Dream – Muchū Mondō, Seizan Yawa (evening conversations held on West Mountain), and Muso Kokushi goroku (Zen no koten). Known generally as Musō Kokushi, his other names include Shogaku Kokushi, Shinso Kokushi, and Fusai Kokushi.

*7 Enshū Kobori

Enshū Kobori (1579 ~ 1647), heir to a samurai family, was versed in tea ceremony and an exceptional landscape architect. He served under Hideyoshi Toyotomi, Ieyasu and Hidetada Tokugawa and also took part in the creation of Sentō Imperial Palace, Sunpu Castle (Shizuoka Prefecture), the Gyoko Palace (elevated Emperor’s seat) at Nijō Castle, as well as the Ninomaru Garden there. His style represents the early 17th century. Versatile in classic Japanese poetry (waka), calligraphy, and especially tea ceremony, he was a famous tea master. Also attained the Buddhist name of Sōhō, and built the Kōhō-an at Daitoku-ji Temple.

*8 Jihei Ogawa (the 7th)

Jihei Ogawa (the 7th) (1860 ~ 1933) a landscape architect of the Meiji, Taisho, and Showa eras. Better known as “Ueji,” the name of his business. Starting with Aritomo Yamagata’s Murin-an Villa garden, he created many Japanese gardens and was a leading influence on modern Japanese landscape architecture. His gardens are based on a naturalistic flow of scenery, liberally using millstones. Some of his famous gardens include Heian Jingu Shrine gardens, Tairyu-Sanso, Maruyama Park, Kaiuso, and Hekiunso in Kyoto, as well as the Kyu-Furukawa Garden in Tokyo.

*9 Jishō-ji Kogetsudai and Ginsadan

Jishō-ji (Ginkaku-ji Temple) Kogetsudai is found at Yoshimasa Ashikaga’s Higashiyama villa that was turned into a Zen temple after his death. Today known as Ginkaku-ji Temple, it is designated as one of the Historic Monuments of Ancient Kyoto under World Heritage sites by UNESCO. In the garden is a flat-topped mound of white sand called Kogetsudai (Moon Viewing Platform) and the Ginsadan sand design. Today, Ginkaku-ji is well known for the Kogetsudai, however it was not part of the original garden and is thought to have been created in the early Edo period when the garden was renovated. It was highly praised by the influential modern artist Tarō Okamoto. It is said that a garden craftsman used his creative artistic sense and raked the sand into a mound so it would look scenic when the pond was being dredged. However, the true motive and the creator are unknown.

*10 The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective

The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective (1989 published by Cambridge ; New York : Cambridge University Press) by Stephen & Rachel Kaplan on the important role nature has in human life through perceptual psychological analysis. The writer, over a course of 12 years, compiled various advantages and sense of satisfaction that natural environment provide through research of the human perception and understanding of nature, what kinds of natural environments we preferr, and the spiritual restorative we can attain from nature.